By: Twyla Vlahon

Generally, child care is either something you care about or something you don’t.

It’s kind of shocking, really. People can go their entire lives barely thinking about child care, but the moment they have a child, or even just decide that they’d like to, what once meant nothing to them is now profoundly important. It’s hard to name many other things that have such a dramatic “on” button. To the large number of people who don’t have children and/or don’t plan on having children, it’s (understandably) easy to gloss over child care in favor of things more directly relevant to their lives. Unless you’re really listening, and sometimes even if you are, child care news is often smothered by more eye-catching stories of politics, crime or war. But when really looking, child care pops up in the news all the time. In 2021, President Biden introduced the Build Back Better Act, a piece of legislation featuring considerable child care reform, including free preschool for all children three to four years old and a cap on child care costs for families. Though this policy never saw the light of day, Biden has continued his push for affordable child care through the CHIPS Act (which is actually about manufacturing instead of daycare, but has a stipulation requiring that semiconductor producers provide for their employees’ child care in order to receive federal funding) and segments of his proposed FY2024 budget. Closer to home, Gov. Pritzger has expanded the Illinois-wide Child Care Assistance Program and extended a plethora of grants for daycare providers. But if child care only matters to some people, why is it legislated so frequently? And if it matters so much to those people, why isn’t it focused on more?

I’ve been thinking about those questions a lot lately. To be completely honest though, I’m somewhat predisposed to. My mother has worked in a daycare all my life, and some of my earliest memories are playing on my Nintendo DS as she and other employees got ready for parents to drop off their children in the morning, or waving at her through the window while my class had recess and she worked inside. Living with my mom, it’s easy to see the impact child care has on people. Standing awkwardly next to her as she talked to parents, daycare-attending children, or fellow daycare employees was a fact of my childhood. All of them would have drastically different lives if they didn’t have access to this service. Not only is it important to them, it’s important to my mom as well. As any parent or babysitter can attest, child care isn’t easy. It’s a physically and mentally demanding job. On top of that, understaffing often leaves my mom and other daycare workers unable to take lunch breaks or sick days, making their difficult job a time-consuming one as well. My mom is frequently exhausted after work, and feels that she’s never able to be with our extended family, especially her grandchildren. But she also worries that if she found a different, less-draining job, her daycare wouldn’t have enough employees and would be forced to shut down, leaving the parents and children they serve with no care. I can list every time Biden or Pritzger have mentioned child care precisely because I make a point of telling my mom about it every time. I remember how excited she got when Biden acknowledged daycare employees as “essential workers” during the pandemic. Never has the conflict between the wildly different levels of interest in child care been more apparent to me than in those moments.

What I’ve come to realize, though, is the parents and children my mom stops to talk to are not the exception, not at all. They’re the rule, and they have a lot more in common with people who never think about daycare than it might seem. Access to child care affects everybody, whether they know it or not. Many of the services people require to get around in the modern world could not be completed without child care. Knowing their children are safe and looked after allows guardians in all job sectors to go to work and provide those services. Besides, everyone needs rest, and even stay-at-home parents can’t spend all of their time tending to their kids. Child care lets families work and rest so that they can continue to live their lives happily and healthily and aid others in doing the same. It also gives children a chance to interact with kids and adults that they may not know in a place they may not be familiar with, building a sense of independence and confidence that they take with them for the rest of their lives.

Child care has a lot of benefits, but those benefits–and child care itself–isn’t very commonly understood by people outside of it. It’s easy to see why; child care is complicated. Information on it isn’t particularly hard to find, a quick Google search brings a variety of reputable sources, but that’s precisely what makes figuring out the system as a whole so difficult. There’s so much information out there that following the logical thread of it all to get to the bottom of how things really work is a struggle at best and a 30-tab rabbit hole at worst (and as the person who did the research for this article, I can attest to that). Though figuring it out the first time is definitely difficult, once you get down to it, child care is quite easy to understand.

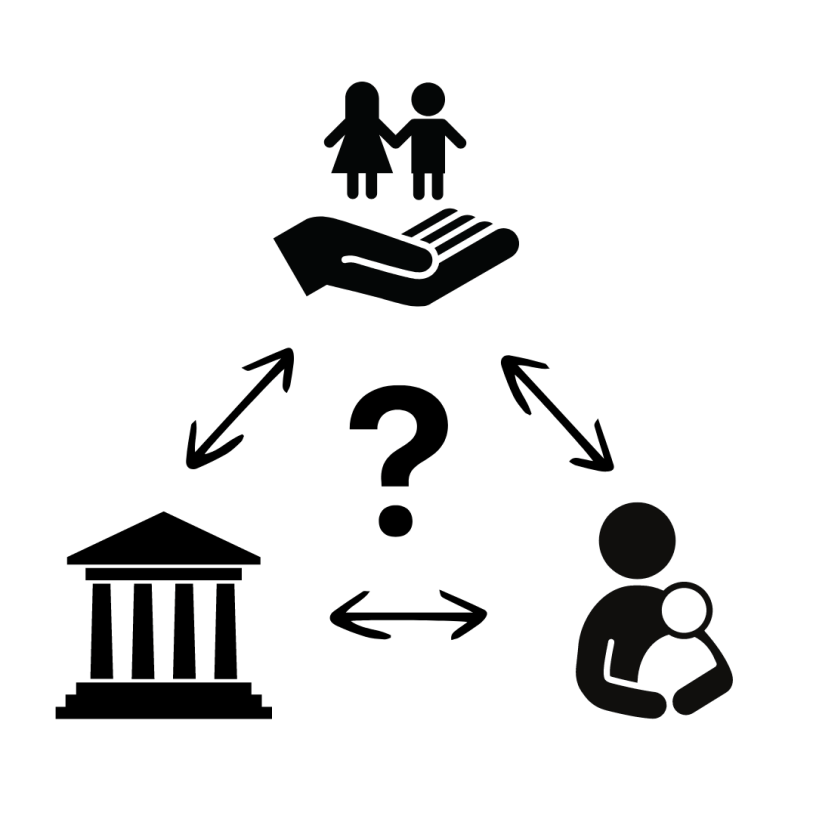

Imagine the current child care system as a triangle, with three points feeding into and supporting each other. These points are the care providers, the families receiving care, and local and federal government agencies. At the top, the providers. These can take many forms, including care centers, private home-based care or friends and family. Providing any kind of service requires money, and one as energy- and resource-intensive as child care is particularly expensive. Adequately tending to children requires food, cleaning supplies, educational materials such as toys and books, and training for workers, not to mention keeping up with parental demands and always-updating understandings of child psychology. Providers have a number of ways to cover these costs, but their main method is tuition. Tuition is paid for by the two supporting members of the triangle, families and government. Families pay providers for taking care of their children and, when they can’t, the government steps in. Low-income families receive state-provided child care subsidies that allow access to care programs they would not otherwise have. Providers allow guardians, including those working in government themselves, to do their jobs and in return those guardians make sure the providers are fairly compensated, whether that be through private-pay tuition or state subsidies. In this way, it seems like the triangle would be effective. Except it isn’t.

In short, this system often fails. The tuition prices that child care providers set are much too low to adequately fund the cost of care. Providers can only set prices at what most families can afford, lest those families take their business somewhere cheaper, meaning providers work under razor-thin margins. This problem existed before the pandemic, but COVID-19 has only made it worse. The cost of care rose with the new need for sanitation supplies and workers to cover for those infected, but the amount families can pay fell with business closures and job loss and has not risen even as the pandemic dwindles. This lack of funds leads to the previously-mentioned understaffing that my mom and her coworkers must deal with, in addition to low wages for the staff that remain. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, the 2021 national average wage for child care workers is $13.22. It’s even lower in Illinois, with the statewide average being $12.85. More often than not, these wages are not reflective of greed or stinginess on the part of child care program directors; they couldn’t raise them if they wanted to.

All of this combined creates a less-than-appealing workplace, to say the least, giving child care programs an absurdly high turnover rate. As asserted by the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (a multi-university research collective dedicated to studying early childhood psychology), children develop stronger relationships with consistent carers. In the current system, children are denied these relationships by a rotating door of stressed and underpaid staff, preventing them from learning the communication and relationship management skills that make child care so beneficial. At its worst, understaffing can lead to program closures, leaving families without care. To avoid this, guardians pay exorbitant prices to ensure their children are not left behind. In the Child Care Aware 2019 report on the price of child care, researchers found that having two children (the 2019 national average was 1.93 children per family) in a child care center exceeded annual median rent payments in every state, and exceeded mortgage payments for homeowners in 40 states and the District of Columbia, and those stats have changed little in the following years. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends the price of child care being no more than 7% of household income, and yet child care prices eat away 10% of the national average income for dual-income households and 35% of the national average income for single-income households. How can the price of child care fall so short in covering provider costs and yet be such a financial burden on families?

The root of this problem is the way government subsidy rates, meant to support families who can’t pay for child care on their own, are set. Each state does a market rate survey every three years, basing their rates on the average price of child care and accounting for variation in geography and type of care. This is where the problems begin. As previously mentioned, providers can only set their prices at what most families can afford. Federal law recommends states set rates at the 75th percentile, or the price at which 75% of child care providers reported charging, meaning that rates are based on a fraction of already diminished prices. These subsidies, though certainly helpful, only scratch the surface of the money that families and providers truly need because they look at only the price of child care to families and not the cost of providing it. Market rate surveys are not the only way to collect subsidy data though. Alternate methods are allowed if the state in question has received federal approval, but they are limited in their usefulness because they only invert the problem by focusing exclusively on cost to providers and ignoring price to families. Alternate methods are also quite uncommon—the only state/territory to apply for and carry out an alternate survey method for the three year survey period 2019-2021 was Washington D.C.—and frequently more lengthy and costly than a market rate survey. But they, along with market rates, are crucial in determining appropriate subsidy amounts that actually support providers and families. Maryland child care officials have expressed an interest in developing a unique market rate survey/alternate method hybrid, but it is unclear when this hybrid method will be formally adopted. Still, it is a valuable step towards updating the child care system that leaves providers and families without the funds they need to do their important work.

This problem, though more directly relevant to some than others, impacts every aspect of society. Workers in all fields struggle if they are unable to get care for their children. Acknowledging the severity of the issue, moves have been made to confront it. As previously mentioned, Biden and Pritzger have made moves to address child care. These are certainly steps, and time will tell whether or not their plans will help in any meaningful way, but even if they do, the plans themselves will never be enough. Part of what makes fixing the child care system so difficult is managing the wildly different audiences of people who care and people who don’t. Most times, the people who do care don’t know what to do, and the people who don’t care would if they knew what was happening, what some are calling a “child care crisis.” The first thing the child system needs right now is education and awareness. It needs people to pay attention, to listen and learn. It needs people to care. What you can do as a citizen is continue to educate yourself on child care problems and policy. Keep your eye on news regarding child care, and try to support local child care providers in whatever way you can, whether that be financially or through a heartfelt “thank you.”More information can be found at https://www.childcareaware.org/, https://developingchild.harvard.edu/, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/wb/topics/featured-child care and https://childcare.gov/consumer-education.